In 1895, a professor by the name of Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen discovered a source of invisible rays which were capable of penetrating materials not normally translucent to ordinary light. Not only this, but these mysterious rays also caused certain chemicals to fluoresce, notably barium platinocyanide. Not creative in choosing names, Wilhem temporarily called these new rays ‘X-Rays’, a name that sticks to this day.

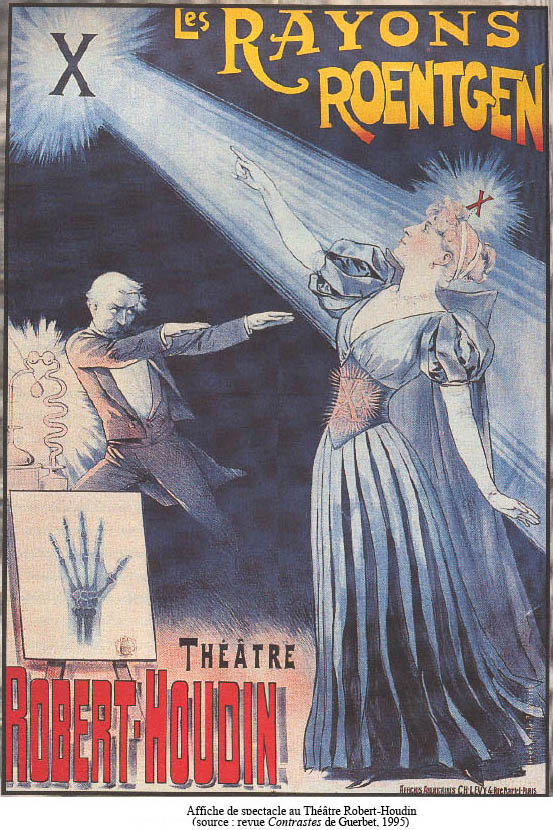

It doesn’t take long for this news to spread, and not too long after speakers at the Grand Cafe on the Bulevard Des Capucines improvise a show to fascinate a crowd of 33 spectators, where their invisible bones are made to cast a shadow on a shimmering screen by means of a Crooke’s tube and rumchoff coil. Similar shows of this nature were held by the Lumière brothers; the men who presented the first film in the history of cinema. In fact, the soon-to-be great filmmaker Georges Méliès assists these demonstrations.

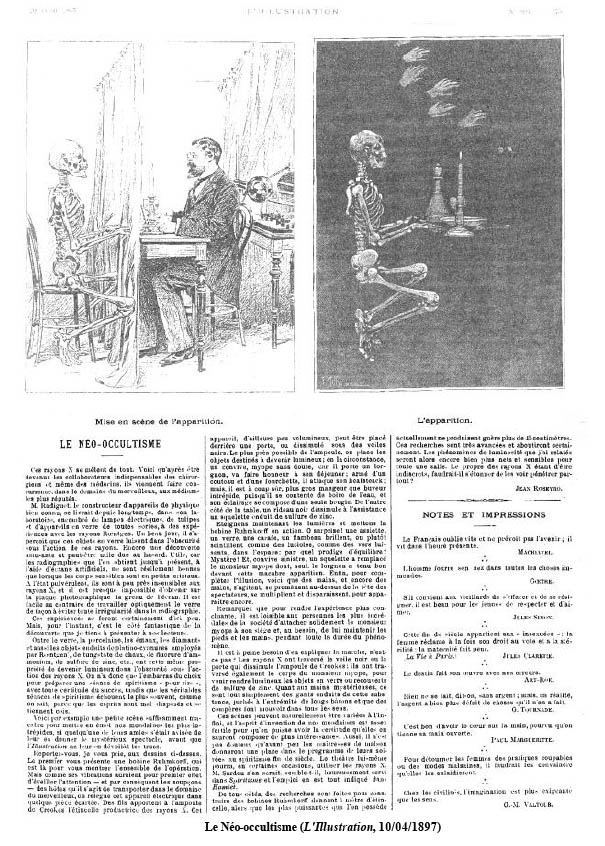

Soon, others exploit this new invention, and only a few months’ time after rontgen’s discovery sideshow men begin to host “neo-occult sessions” during which painted items are made to fluoresce in the presence of a wide x-ray beam. Often these objects were skeletons or items of a similar deathly nature, and fortunes were told to those who paid their sum.

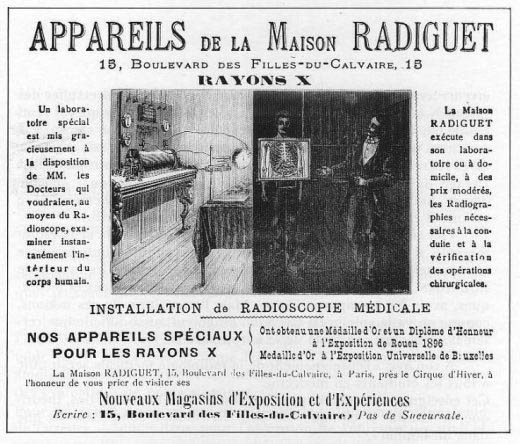

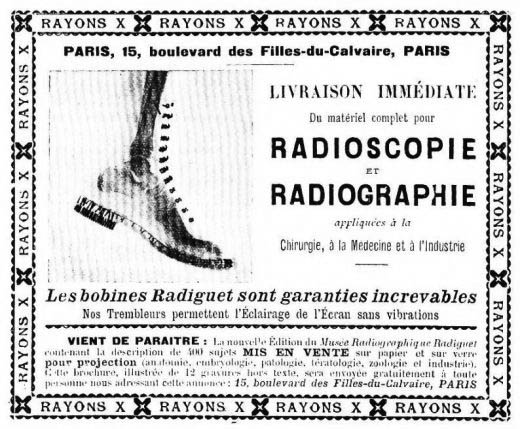

These sessions became so popular that some retailers even began to stock items related to this type of service. This practice peaked circa 1900.

Throughout 1896, x-rays gradually are applied to nonscientific applications. Despite some initial opposition, x-rays find their place almost instantaneously in the world of medicine and surgery.

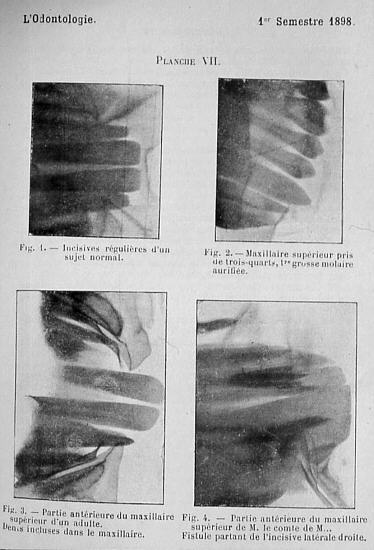

A dental radiograph taken by Dr. Walkhoff, 14 days after Rontgen’s paper was published. Walkhoff reported that the 25 minute exposure “was a real torture, but I felt great joy in seeing the results when I realized the importance of Röntgen radiation for our specialty”.

In the USA, many doctors send their patients to be radiographed in physicists’ laboratories. Wolfram Fuch, an electrical engineer employed by one of these laboratories, had conducted more than 1400 radiographs by late 1896.

The first practitioner to use x-ray therapy is likely Dr. Leopold Freund of Vienna, where his first patient was a five year old girl with a hairy beauty mark on her back. In December 1896 she underwent an x-ray treatment 2 hours per day for 16 days, where after 12 days the hair began to fall out, but her back became horribly inflamed. After this incident, Freund limited subsequent exposures to 10 minutes.

At this time it was usually the private radiographer’s duty to assess the fluoroscopic images and report back to the doctor with the news. This began to change with Dr. Antoine Béclère was the first notable doctor to directly image his patients. His colleagues accused him [of] “dishonor by becoming the medical photographer!”

In 1897 Béclère created the first in-house radiology laboratory in Hôpital Tenon, where x-rays were usually performed by Richard Chauvin and Félix Allard.

Still, at that time any engineer, builder, pharmacist, merchant or wine dealer could open their own “x-ray laboratory”. Before 1900 it was often assumed that anyone competent enough to be a good photographer could interpret a radiograph.

Still, at that time any engineer, builder, pharmacist, merchant or wine dealer could open their own “x-ray laboratory”. Before 1900 it was often assumed that anyone competent enough to be a good photographer could interpret a radiograph.

Of course, many manufacturers began to compete a market that promised to be a big one. Their salesmen often offered themselves as demonstrations to the deep-pocketed physicians, where they soon discover the effects of such repeated exposure.

In September 1896. A man was shot in the head but was not killed. Only after 3 hours of irradiation is the bullet located.

In November 27, 1897, fluoroscopy was used to help deliver a newborn child. In June 1896, the famed Thomas Edison developed a Calcium Tungstate flouoscope which allowed for bright, real-time observation of a patient’s body. Edison clearly instructs that the success of this method depends on the power of the Crookes tube used, that is to say, the voltage used across the tube. Thus, nearly 90% of these x-rays make it to the face of the unfortunate doctor preforming the procedure.

Signs of something amiss…

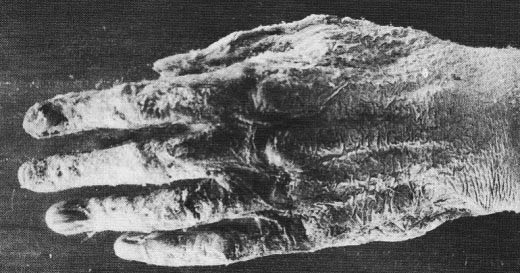

In November of 1896, an article titled “the misdeeds of x-rays’ appeared in Nature, where the case of an x-ray exhibitor in London was studied. During the year’s summer, a man was paid to publicly demonstrate x-rays at various fairs for for several hours a day, where he soon developed some curious ailments.

“In the first two or three weeks I felt no inconvenience, but after some time numerous dark spots appeared on the fingers of my right hand which the x-rays often pierced. Gradually they became very painful; the rest of the skin was red and inflamed strongly. My hand hurt so much that I was constantly forced to bathe it in cold water. Ointment temporarily calmed the pain, but the skin had dried and become as hard and as yellow as parchment, and completely insensitive. I was not surprised when my hand began to peel.”

“Soon the skin and nails fall off and the fingers swelled, the pain remaining constant. I lost the skin of my right and left hands, and four of my nails have disappeared from the right hand and two left and three others were ready to fall off. During more than six weeks I was unable to hold anything in my right hand and I can not hold a pen since the loss of my nails … “

Interestingly, not much attention is paid to the article.

The first man to die as a direct result of x-ray exposure is likely Clarence Madison Dally, an assistant to Thomas Edison. Clarence tested every x-ray tube he produced on his hands, which, over the course of several years caused him to develop a cancer of the hand. In 1900, despite several futile amputations he died of metastatic cancer; an event that reportedly caused Edison to abandon all experimentation with x-rays.

The first man to die as a direct result of x-ray exposure is likely Clarence Madison Dally, an assistant to Thomas Edison. Clarence tested every x-ray tube he produced on his hands, which, over the course of several years caused him to develop a cancer of the hand. In 1900, despite several futile amputations he died of metastatic cancer; an event that reportedly caused Edison to abandon all experimentation with x-rays.

In 1903, when asked about the event Edison replied, ‘Don’t talk to me about X-rays, I am afraid of them”.

In 1900, early radiologist Dr. Mihran Kassabian began to share his concerns regarding the x-ray as a possible irritant after noticing burns developing on his hands. Over the years, he becomes increasingly weary of x-rays and urges for more caution and regulation in their use as a therapeutic technique.

In 1900, early radiologist Dr. Mihran Kassabian began to share his concerns regarding the x-ray as a possible irritant after noticing burns developing on his hands. Over the years, he becomes increasingly weary of x-rays and urges for more caution and regulation in their use as a therapeutic technique.

Somewhat ironically, he eventually developed a serious cancer of the hands, and succumbs to Dally’s same fate in 1910.

Continued fun with ‘A new kind of ray’

By now, some are beginning to understand the dangers of x-rays and steps are taken to ensure radiographers are safe. Lead glass bowls are placed around x-ray tubes to shield excess radiation, and the invention of the Coolidge tube helps to make exposures faster and safer for all parties involved. Still, the public is largely unaware of their danger.

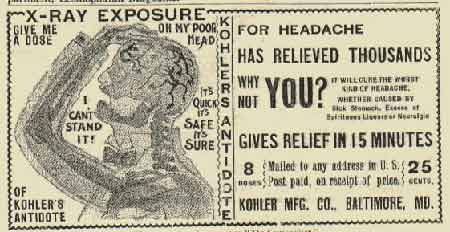

For practitioners of quackery, x-rays became a godsend. For millions, the mysterious ray offered the promise of pain relief, disease therapy, addiction curing; even treatment of skin blemishes.

For practitioners of quackery, x-rays became a godsend. For millions, the mysterious ray offered the promise of pain relief, disease therapy, addiction curing; even treatment of skin blemishes.

For only a few dollars, you too could be cured of sexual impotence!

For some time they were even viewed as a new form of artistic photography, and journalists were encouraged to use them as such.

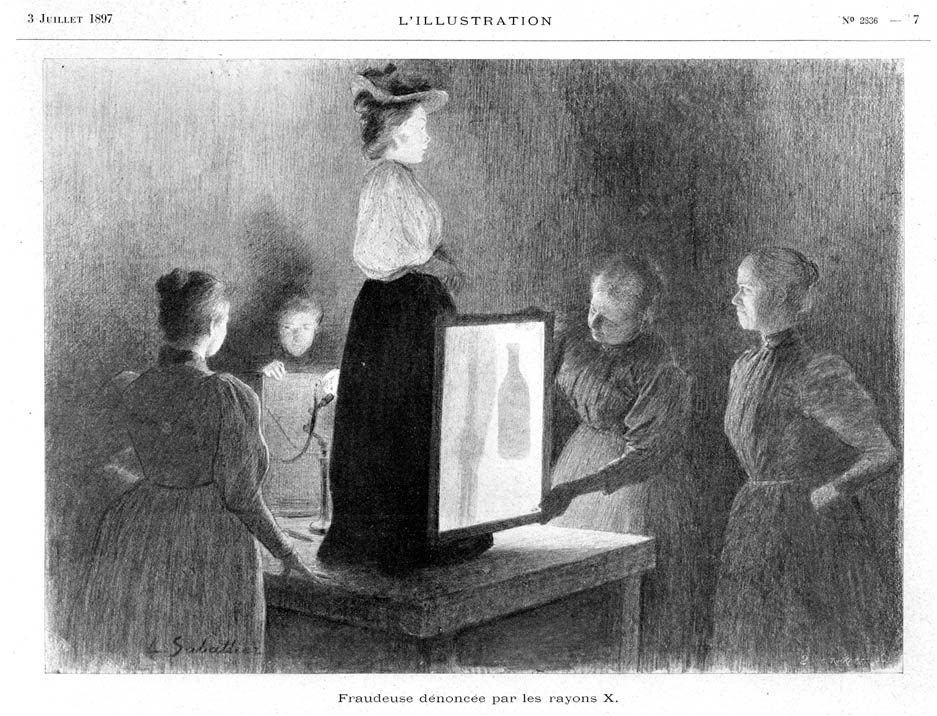

Law enforcement agencies, interested in inspecting packages and luggage, bought these new ‘cameras’ by the dozens. It was not uncommon for them to be used frivolously, though.

‘Human Telescopes’ –a crude form of fluoroscope, became fun party toys among the elite, where they offered a new use for those Crooke’s tubes which were ever-so popular novelties back then.

‘Human Telescopes’ –a crude form of fluoroscope, became fun party toys among the elite, where they offered a new use for those Crooke’s tubes which were ever-so popular novelties back then.

Much like radio communication, radiography even became a fun hobby for those who could afford the necessary equipment. [Not to say that it this is untrue today!]

In reality, these machines did little to help fit the shoe.

A wake up call…

Interestingly, it wasn’t the x-ray which made known the fact that ionizing radiation wasn’t something to play with. Rather, it was the mishaps of the similar novelty of the time, Radium, which put an end to most of the nonsense.

Radium is an element that emits huge quantities of alpha particles and gamma rays; which, like x-rays, “Had the power to cure any ailment”. As such, it was added to everything from wristbands to drinking water and was bought by the public en masse.

Circa 1917, thousands of women were working in shops to paint the dials of watches with radium-containing luminescent paint. Ideally, this wouldn’t have been anything special, but unfortunately paintbrushes lose their shape after a few strokes. To keep them sharp, women would use their mouths to adjust their shape.

Circa 1917, thousands of women were working in shops to paint the dials of watches with radium-containing luminescent paint. Ideally, this wouldn’t have been anything special, but unfortunately paintbrushes lose their shape after a few strokes. To keep them sharp, women would use their mouths to adjust their shape.

Many women eventually died of radium jaw; a disease of the bone that often results in the jaw literally falling off. This, coupled with the death of socialite Eben Byers finally let the public know, large amounts of radiation are dangerous. ∎

Hellbrunn

Can you tell me where you found the information about Lumiere and Melies assisting x-ray demonstrations? I am aware that Melies made several films about x-rays in the 1890s, but I was not aware that they assisted in fluoroscope demos.

TajanaT

I absolutely LOVE your wesite. Totally inspired me for a lecture I am about to give.

Great, great work.